Overview

The following information for this section is based on the Acting-Out Cycle and is adapted from Managing the Cycle of Acting-Out Behavior in the Classroom by Geoffrey Colvin.

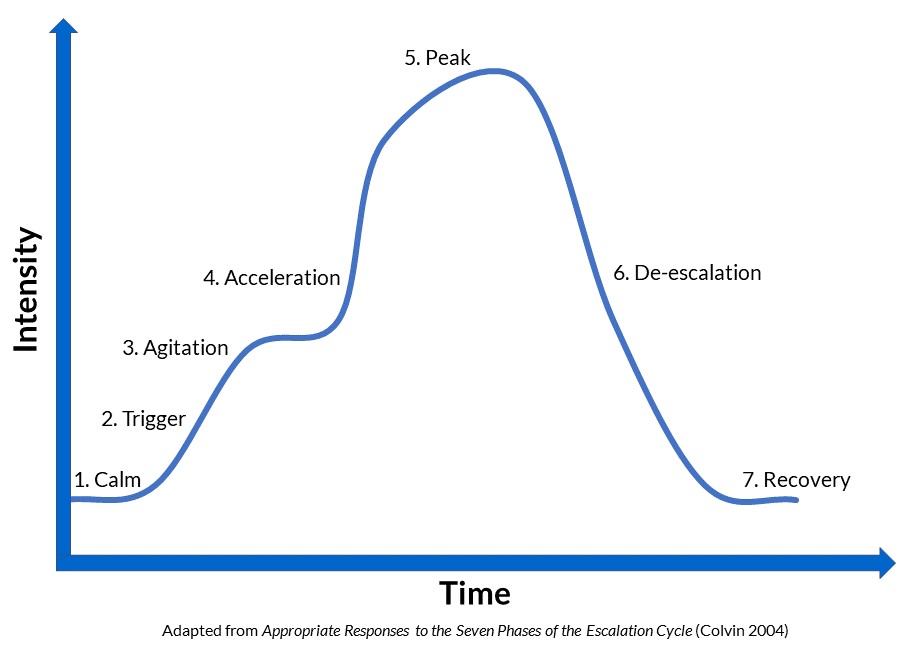

The Acting-Out Cycle is a model of how a student's behavioral response often occurs in phases. However, the Acting-Out cycle (diagram below) is not just a tool to understand a student’s emotional and behavioral responses to a trigger. The Acting-Out cycle is most useful as a guide for how adults should respond to students to assist with de-escalation. Adults who effectively and timely intervene can prevent intense behavior responses from occurring and minimize or de-escalate such behavior when it does occur. See the Prevention and De-escalation of Intense Behavior Responses: What Adults Can Do section in this series for more information on how to use the Acting-Out Cycle to respond to student behavior.

The purpose of this section is to understand the specific features of each phase in the cycle to help adults have some level of predictability in planning to meet student needs, as well as success in interrupting the cycle before behavior escalates (Colvin 2004). The specific phases that describe student and adult behavioral responses in the response cycle are depicted in the graphic and narrative that follow.

Student and Adult Behavioral Responses in the Response Cycle

1. Calm Phase

Student Response: During the Calm Phase, the student may be engaged in instruction and classroom activities.

Adult Response: Adults who have strong and healthy relationships with students are more likely to support students in the Calm Phase. In addition, adults can support a calm learning environment by ensuring that social and behavioral expectations are clear and explicitly taught, that there are predictable routines and procedures, and that learning activities are engaging. Using the CEC and CEEDAR Center High Leverage Practices (HLPs) in Special Education, such as providing students with positive and constructive feedback to guide student’s learning and behavior, can help students remain in the Calm Phase. It is during this phase that additional proactive and preventative HLPs can be utilized, including scaffolding supports, using assistive and instructional technologies, flexible grouping, adapting curriculum tasks and materials for specific learning goals, and teaching and modeling social and emotional learning competencies.

Specially designed instruction can also be utilized proactively to teach students to recognize their own physical state and learn strategies to stay in the Calm Phase. Specially designed instruction should be based on each student’s individual disability-related needs and may include teaching skills in self-regulation, problem solving, flexibility, peer-mediated instruction and interventions, or other SEL competencies. Supplementary aids and services that address a student’s disability-related needs can also support students to remain in the Calm Phase. Supplementary aids and services may include sensory supports, visual boundaries, visual schedules, accessible educational materials, and assistive technology.

2. Trigger Phase

Student Response: Typically something happens in the student’s environment that acts as a trigger. A trigger is unique to each student and can be caused by an unaddressed concern, unsolved problem, or unmet need of the student. It may be something in the environment or in the situation that caused an intense response. The trigger may be school-based, such as a negative interaction with a peer, change in schedule, or confusion about an assignment, or non school-based, such as a negative interaction with a family member, lack of sleep, or feeling ill. The Trigger Phase is important to understand because how the student and adult respond during the Trigger Phase has an effect on whether the student de-escalates, escalates to the next phase, or jumps to a more intensive phase.

Adult Response: Adults can support students by engaging in discussions to learn about each student’s unique triggers and model with students how they manage their own triggers. Use of an instructional tool to teach self management, such as The Incredible Five Point Scale, can help students identify triggers, identify how those triggers make them feel, and assist students with engaging in problem-solving with adults to identify proactive responses to triggers.

Once triggers are identified, adults can use positive supports, prompts, visual supports, social narratives, reinforcement of desired behavior, or other preventative strategies to help students anticipate, avoid, or effectively respond to triggers and get back on track. Preventative strategies during the Trigger Phase can prevent the escalation of student behavior into more serious phases of the cycle. When triggers are present, an adult can help break the cycle and redirect the student back to the calm phase by increasing opportunities for a sense of success and belonging and reinforcing the social and emotional learning skills that have been taught.

3. Agitation Phase

Student Response: In the Agitation Phase, the student’s emotions and behavioral responses begin to gain energy. The Agitation Phase can last a long time and the student may become unfocused or disconnected from the learning activities. Signs of agitation can include restlessness, off-task behavior, starting and stopping work, moving the body in some way, vocalizing concerns, tapping feet or hands, moving the eyes around, disengagement, or staring off in the distance.

Adult Response: It is important that adults intervene early in the Agitation Phase because it is possible that typical or improperly selected intervention strategies might escalate the behavior if the student has been in the Agitation Phase for a long time. The goal in the Agitation Phase is to restore calm and offer support. Adult intervention is most effective if it is properly selected and meets the individual needs of the student. Calming a student in the Agitation Phase can be as simple as giving focused positive attention to the student, providing a break, or gently redirecting the student toward a different activity. Another approach is to verbalize and acknowledge to the student that the adult recognizes the student is struggling and ask how the adult can help. Overall, the adult needs to show empathy and help reduce the student’s anxiety or frustration. Having a strong and healthy relationship with the student informs the best individualized approach to meet the student’s needs, and may serve to calm and support the student during this phase.

4. Acceleration Phase

Student Response: Although the Acceleration Phase falls in the middle of the Acting-Out Cycle (indicating that the behavioral response has been building for some time), this is often when adults first recognize that a student is in distress. It is during this phase that the student exhibits an increase in the frequency or intensity of behavior that interferes with learning. The student may demonstrate a physical reaction in response to the trigger or from the build up of strong emotions and anxiety as the student has escalated. These may include behaviors that interfere with the student engaging in routine daily activities consistent with the cultural or ethnic norms of the student or the student’s community. The student may demonstrate isolation from peers or avoidance of social interactions impacting the student’s access and engagement in instructional activities.

Adult Response: With careful observation and the foundation of a strong and healthy relationship with the student, adult responses during the Acceleration Phase can help avoid many situations that potentially escalate the student to reach the Peak Phase of the cycle. The goal of adult responses to student behavior that interferes with learning should always be prevention. However, some students move rapidly through the cycle and some triggers may escalate or jump directly to the acceleration phase. When this happens, adults might be unable to intervene quickly enough to prevent further escalation of behaviors.

When a student accelerates, the response of adults should be to quickly take note of their own behavior so as to not accelerate along with the student and instead remain calm to help the student regain calm. Adults staying calm may mean the adult does not address or engage the student verbally or physically while the student is demonstrating behaviors that interfere with learning. The hardest part of this strategy is letting go of the idea that all behavior that interferes with learning must be corrected, punished, or verbally or physically engaged with immediately.

When any person, including a student, is agitated, they are not able to effectively reason, problem solve, or communicate verbally. In contrast, being forced to reason, problem solve, or communicate verbally often leads to further physical or verbal escalation of behavior. During these times, the most important course of action for adults is to avoid power struggles and provide time for the student to return to a calm state so the student can re-engage in problem-solving and learning. Some students in the acceleration phase may be able to follow direct and short step-by-step instructions if provided in a calm and clear tone. If the student is predicted to respond to verbal instructions when agitated, adults should ensure that after the direction is given they provide the student with space and time to respond.

The student’s physical and verbal responses during the Acceleration Phase are likely to be a trigger for adult behavioral responses. To remain non-confrontational, adults should pay specific attention to their own physical, verbal, and nonverbal reactions such as proximity, body language, tone of voice, and the number of words and directions they communicate. Adults should co-regulate by using strategies such as relaxation or other self-regulation techniques such as regulated breathing. When student behavior accelerates, it can be difficult for adults to perceive the passing of time. Using strategies such as silently counting down time internally can help ensure the student is given space to respond and also allows the adult to assess the safety of the physical environment and students.

In The ECLIPSE Model (Moyer, 2008), Dr. Sherry Moyer provides suggestions on “magic statements” adults can make that maintain a student’s dignity when they are in the Acceleration Phase. Some examples include: “What can I do to make things better?” “Do you need more time to finish what you are doing?” “I will help you figure this out when you are calm enough to problem solve.” “I understand that you are upset.” “You have a right to your feelings.” If an adult attempts to assert authority, engage in a power struggle, or give ultimatums, it will only serve to increase the tension and intensity of the student's emotional state and may push the student into the Peak Phase.

How the adult responds to the student during the Acceleration Phase can have a long lasting impact on the safe and healthy relationship that has been built with the student. Thus, it is important for adults to demonstrate respect towards the student and wait whenever possible to speak to the student in private to debrief about the trigger, the student and adult’s responses, and problem-solve next steps. More recommendations on adult behaviors to assist with de-escalation can be found in the Prevention and De-escalation section of this series.

5. Peak Phase

Student Response: During the Peak Phase, the student is at the greatest risk of engaging in a behavior that could endanger the safety of the student or others. The student may scream, destroy property, cry, or escalate to the point where they have hurt themselves or others. At this point in the cycle, the student is not in control of their physical and verbal actions.

Adult Response: The adult response during the peak phase should focus on ensuring the safety of the student and others. While the Peak Phase is often a short phase, it can be traumatic for the student and for others who witness it. Similar to the Acceleration Phase, the adult needs to remain calm and attend to their physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors to help the student return to calm and to help other students feel safe. Schools should have a Safety Plan with a specific protocol for responding to this type of student behavior and everyone should know how and when to implement the plan. Because a student’s behavior has peaked does not mean physical intervention from the adult is required or helpful. Physical intervention should never be used when a student does not demonstrate a clear, present, and imminent risk to the safety of the student or others. For example physical intervention would not be needed for behaviors such as crying, screaming, swearing, or damage to property when the damage poses no risk to the student or others.

6. De-escalation Phase

Student Response: As the student enters the De-escalation Phase, they may be confused, disoriented, or embarrassed. Some students will try to reconcile with those around them, seek adult comfort and communication, or want to talk about why they became upset. Other students may withdraw, deny any responsibility or involvement, or attempt to blame others. In other words, some students may want to engage in debriefing and problem solving about the incident right away, while other students will need space and time before they are best able to engage in debriefing and problem solving.

Adult Response: Most students are receptive to adult direction during the De-escalation Phase and need to be given a way to get out of the situation with dignity. The adult should reduce the amount of directions and demands put on the student as well as reduce the amount of verbal interaction between the student and others in the learning environment to provide the student with space and time to calm down. As mentioned in the Acceleration Phase, the adult should demonstrate respect to the student and find a private location to debrief about the trigger, the student and adult’s responses, and problem-solve next steps. If a private location to discuss the incident is not immediately available, give the student an activity that can be completed independently and away from any additional potential triggers or distractions. When the adult and student are both completely calm, then move to the Recovery Phase.

7. Recovery Phase

Student Response: In the Recovery Phase, when both the student and the adult are calm, the student is best able to debrief and problem-solve about the incident. Debriefing about both the student and adult’s responses during the incident, and problem-solving next steps is always encouraged. Debriefing is a learning opportunity for both the adult and the student and it supports strong and healthy student-teacher relationships. Failing to debrief after a student has de-escalated can have the unintended consequences of communicating lower expectations, like that the adult does not care, or may even reinforce behaviors that interfere with learning.

The adult should use the incident as a teachable moment and review what happened with the student by first listening to the student’s perspective of the incident using active listening. After the student has shared, the adult can add their point of view as to what might have triggered the incident. Together, the adult and student should make a plan for how the student thinks they can best get their needs met and how the adult can help the student avoid or manage triggers in the future. The discussion should include the student’s thoughts, with adult input and guidance, on new strategies to use for calming down, establishing words to help express emotions, or other social and emotional skills that need to be taught and practiced. If there was a major interruption of other students’ activities, there may also be a need to debrief with the whole class. When doing this, it is important to keep student privacy and dignity in mind. It is also important for adults to self-reflect on how they might have reacted differently during the Acting-Out Cycle.

There are many resources, interventions, and programs available to help adults debrief and problem-solve with students across age and developmental levels. These include strategies such as using social autopsies, Social Behavior Mapping™, the RENEW program, and the Incredible Five Point Scale, as well as developing social narratives such as power cards, cartooning, or Social Stories™.

In all phases, the adults must be aware of the individual nature of a student’s response. Any adults who work with the student must have access to and be able to implement a student’s IEP, BIP or 504-plan, including when the plan specifies behavioral interventions. A student’s plan may include specific adult responses, interventions, accommodations, or other supports that are individualized for the student. Adults should know and be ready to implement any specific adult responses for each phase in the cycle.

At each phase of the cycle, adults have a variety of choices to make when addressing a student’s behavior that interferes with learning. Ultimately, it is the adults, not the students, who have the developmental social and emotional competency, responsibility, and ability to choose to either escalate or de-escalate the situation by their response to the student. Adults should be aware of when a student is triggered and should always respond, albeit with supportive, preventative strategies rather than with power struggles and punitive techniques. Adults can choose a route that will serve to de-escalate the situation if they are calm and intentional in their approach.

Reflection and Application Activities

The following reflection and application activities were developed to build the knowledge, skills, and systems of adults so they can assist students with accessing, engaging, and making progress in age or grade level curriculum, instruction, environments, and activities.

-

Review each phase of the cycle individually or with your team.

-

What do you notice about the student and adult responses across all the cycles?

-

Which phases in the cycle do you feel you and your colleagues are best able to support students? Which do you feel you need the most professional learning and development to support students?

-

What are the proactive and deescalation strategies listed above that you and your colleagues currently use? For each phase in the cycle, what are the additional strategies you or your colleagues use?

-

-

Review the Trigger Phase and Agitation Phase.

-

Identify your own triggers that you have experienced in either the school or other environments that lead to the Agitation Phase.

-

What behaviors from others around you either escalate or de-escalate your responses in the Agitation Phase?

-

What self regulation or other internal strategies do you use to help de-escalate yourself away from the Agitation Phase?

-

Why do you think it is important for adults and students to know and understand their triggers?

-

What systems do you have in place in your classroom, school, or district to help students identify their triggers and problem solve strategies for responding to triggers?

-

Consider the trigger for an individual student. Was the trigger something you, another adult, or another student said (e.g., microaggression) that triggered a student? The key strategy to use when a microaggression is committed is to apologize. When a student is triggered, how do you think you could apologize for something that was said or done in order to de-escalate the behavior and maintain the relationship?

-

-

Are there patterns of if, how, and when adults respond to student behaviors based on race or ability (e.g., disability category)?

-

What data and information is collected and analyzed to identify if there are race or ability-based patterns for how adults respond to student behavior?

-

How might data help identify which adults need additional training and support to respond to student behaviors?

-

How often is data disaggregated to ensure adults are responding to student behavior consistently across the school and district?

-

-

How does the response cycle assist with thinking about adult and student behaviors, thoughts, emotions, and reactions when a student is triggered and begins to move through the cycle?

-

Are there students that you have observed who either move rapidly through the response cycle or appear to jump from the Calm to the Peak phase immediately after being triggered?

-

What are some ways to intensify instruction, provide additional accommodation or support, and further remove barriers that either reduce the likelihood of introducing triggers into the student’s environment or better assist the student in managing triggers?

-

Often students may be moving through the Agitation and Acceleration phases without noticing they are escalating.

-

Are there any self-monitoring tools or interventions that may assist students with recognizing their emotional and physical states?

-

How is self-monitoring modeled and integrated into the daily schedule for both individual students needing additional support as well as classroom systems to benefit all students?

-

-

Resources

The following are resources for understanding de-escalation and strategies for de-escalating or preventing intense student behavior.

-

Crisis Prevention Institute

This institute provides trainings to help staff prepare for and reduce crisis situations.

-

The Incredible 5-Point Scale

This is a tool that can be used to teach social understanding. It provides a visual representation of social behaviors, emotions, and abstract ideas. -

Intervention Central

Intervention Central provides teachers, schools, and districts with free resources to help learners who are in need of additional supports for academic or behavioral reasons. -

The Iris Center

The IRIS Center develops and disseminates free online resources about evidence-based instructional and behavioral practices to support the education of all students, particularly struggling learners and those with disabilities. -

RENEW

RENEW is a structured school-to-career transition planning and individualized wraparound process for youth with emotional and behavioral challenges. -

Social Thinking

This is a methodology that promotes the use of visual supports, modeling, naturalistic teaching, and self-management.-

Social Behavioral Mapping™ is a visual template that helps users figure out the hidden social rules of a given situation based on what is happening and the people present.

-

-

Successful Schools

This organization provides resources and professional development on practical skills for creating positive and effective learning environments that meet the needs of all children. -

Zones of Regulation - This framework is designed to foster self-regulation and emotional control skills.

-

To learn more about social narratives, social autopsies, visual schedules, visual boundaries, peer mediated instruction and intervention, and other evidence-based practices referenced in this document, go to the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDCASD), Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules (AFIRM), or Autism Internet Modules (AIM).

References

Colvin, Geoff. 2004. Managing the cycle of acting-out behavior in the classroom. Eugene, OR: Behavior Associates.

IRIS Center. “Understanding the Acting-Out Cycle.” Accessed March 11, 2021. https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/bi1/

Moyer, Sherry A. 2009. The ECLIPSE Model: Teaching self-regulation, executive function, attribution, and sensory awareness, in students with Asperger Syndrome, high-functioning autism and related disorders. Shawnee Missions, KS: AAPC.