Overview

Prevention is the most efficient intervention adults can employ for addressing behaviors that interfere with learning. The more proactive adults can be in supporting students who demonstrate behaviors that interfere with learning, the more successful they will be in helping students learn and maintain new skills to support lifelong learning. When an unanticipated incident occurs, or when a student demonstrates an unexpected behavior that interferes with learning, the manner in which adults respond will influence the student’s response.

Adult responses to student behavior can serve to either escalate or de-escalate the student’s behavior. Adults are not always aware of how their own behavior may inadvertently escalate the behavior of a student they are trying to support, even as they do their best to ensure student safety and uphold classroom and school expectations. When adults use effective de-escalation techniques as a student’s behavior is becoming more intense, they have a unique opportunity to prevent intense behavioral responses or other student behavior that often leads to disciplinary removal, stigmatization, marginalization, or harm to the student or others.

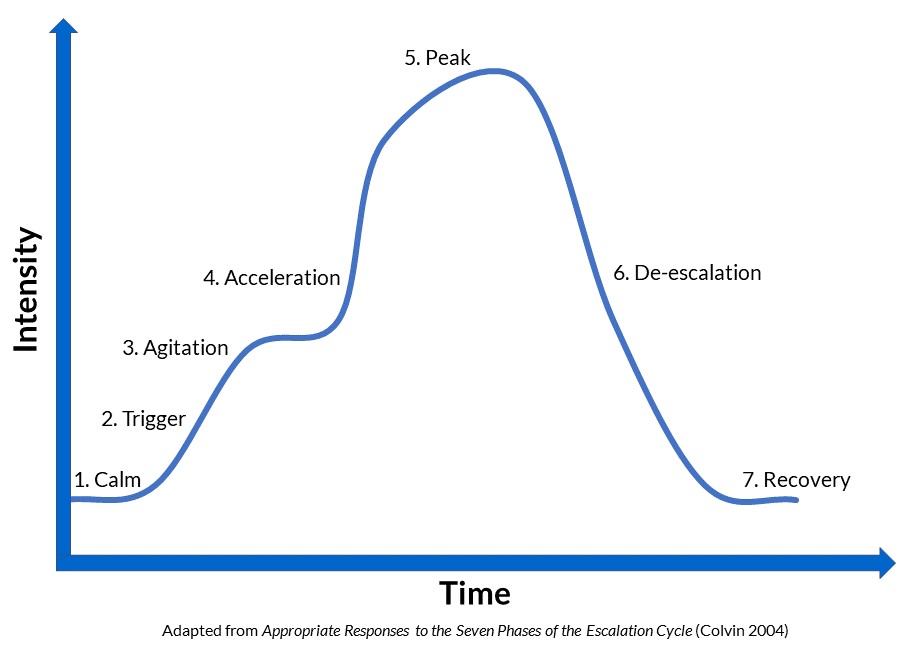

Understanding effective ways to de-escalate student behavior and support prosocial replacement behavior is a critical skill for adults to understand and consistently use. Most students and adults can identify with the emotions, feelings, and behaviors associated with the Acting-Out Cycle when a trigger for stress is presented or when the safety of self or others feels threatened (Colvin 2004). The Acting-Out Cycle (diagram below) is not just a tool to understand a student’s emotional and behavioral responses to a trigger. The Acting-Out Cycle is most useful as a guide for how adults should respond to students to assist with de-escalation. When a student is triggered, adults have the ability and responsibility to assist with de-escalation to help prevent the student from accelerating or peaking. Adult support to assist with de-escalation is necessary, as it takes time for students, especially students with significant behavioral needs, to learn and develop self-monitoring and regulation skills.

For a narrative of this graphic click here.

For more information on the Acting-Out Cycle, see the Response Cycle section in this series.

The strategies below outline adult responses that either support de-escalation or unintentionally escalate a student’s behavior responses in the Acting-Out Cycle.

|

Adult Responses that May De-escalate or Prevent Intense Behavior |

Adult Responses that May Escalate Intense Behavior |

|

Ensure your response to the student is culturally responsive. Utilize culturally responsive problem-solving and the model to inform culturally responsive practice resources to improve your understanding of how to identify and respond to individual student culture and norms. |

Do not assume all students and adults understand the meaning of words in the same way (e.g., cultural differences in interpreting meaning of words or phrases), as well as how they interpret non-verbal behavior, physical behavior or proximity, and what behaviors are expected or not expected depending on context, setting, and adult or student roles. |

|

Limit the number of individuals interacting with the student. The adult with the best relationship with the student should be communicating and providing support. |

Do not overwhelm the student with conversation, additional sensory stimulation, or people. |

|

Model calm through your breath, nonverbal expression, self-talk, tone of voice, and use of calming strategies. The more upset the student becomes, the calmer the adult needs to become. |

Avoid power struggle. Power struggles increase the intensity of the student’s behavior. A loud tone of voice and close proximity when it is not needed can be signs of a power struggle. Be careful not to set up a win-lose situation by making demands or ultimatums the student will not be able to meet in their current state of heightened emotion. |

|

Adult Responses that May De-escalate or Prevent Intense Behavior |

Adult Responses that May Escalate Intense Behavior |

|

Wait for a later time to discuss the behavior with the student. Only after everyone is calm and back in a rational state of mind should there be any discussion. |

Avoid the threat of consequence or punishment during escalation. Punishment does not de-escalate behavior. It is not aligned with the functions of behavior, does not serve to calm the student, and does not teach replacement behaviors. |

|

Pre-teach, prior to a student escalating, how to self-monitor tension levels and use self-regulation strategies for alleviating tension. This instruction can not take place during an incident of heightened emotion. |

Do not expect a student to access a skill that they have not been taught, have not been taught to proficiency, or have not been taught to expand across environments. Learning new skills can take a large amount of time, especially for students with significant behavioral needs. |

|

Know and be able to implement a student’s IEP, BIP or 504-plan that specifies behavioral interventions. Follow the specific responses or accommodations that are individualized for the student, especially with regard to the necessary adult support or approach that best meets that student’s needs |

Do not improvise or deviate from the written plan. Consistency in the adults’ approach will help de-escalate an intense behavior and support a student in learning, applying or generalizing a skill. |

|

Pause and engage in active listening to show that you are listening to the student and that you understand and respect their feelings. |

Do not argue, interrupt, talk over, mock, make threats, or set demands and limits the student is unlikely to meet. |

|

Always validate a students’ feelings. Use language that validates the student’s feelings and not the student’s behavior. Validating a student’s feelings does not mean you validate the behavior. |

Do not tell a student not to be upset, angry, sad, etc. Telling a person not to feel whatever they are feeling can be harmful and escalate the situation. |

|

Be sincere in trying to resolve the situation through your words and actions. |

Do not make statements or judgments about the student as a person, such as “You are a disruptive student. |

|

Ignore any challenging questions from the student and focus only on working with the student toward a calm solution. |

Do not use generalizations, such as “You always get so angry when…”, “You never listen when….” |

|

Adult Responses that May De-escalate or Prevent Intense Behavior |

Adult Responses that May Escalate Intense Behavior |

|

Use a calm, clear, respectful, and non-emotional tone of voice. |

Do not use sarcasm, humiliation, or character attacks. |

|

Stand at an angle to the student. This is less threatening than directly facing them. |

Do not invade a student’s personal space. |

|

Use a non-confrontational stance (arms at the side, relaxed body posture, neutral facial expression) when approaching a student who is agitated, and consider whether approaching a student or backing away is the best option. |

Do not make physical contact or use force. The use of seclusion or physical restraint is prohibited by law, unless a student’s behavior presents a clear, present, and imminent risk to the physical safety of the student or others, and it is the least restrictive intervention feasible. 2019 Wis. Act 118. |

|

Honor the student’s personal space and use caution when considering physical contact with the student. For some students, what an adult perceives as a reassuring touch on the shoulder or an attempt at calm redirection may feel threatening and escalate behavior for an individual student. |

Do not cause the student to feel cornered, threatened, or violated within their personal space. Do not assume that your intent for physical engagement, physical support, or redirection is the same as what is perceived by an individual student. |

|

Use words, body language, and prompts that reduce tension, communicate support, and provide calm redirection. |

Do not plead, nag, yell, or preach. Do not use body language that can be interpreted as frustrated (e.g., arms crossed, pointed finger, scowl, frown, shaking head, roll eyes). |

|

Know and follow your school or district policy related to contacting the police or emergency services. |

Do not call the police outside of your school or district policies. Do not threaten to call the police in an attempt to manage a student’s behavior. |

|

Engage in self-care to ensure you are addressing your own needs and avoid burnout. Adults are only as able to support their students' social and emotional needs as they are able to support their own needs. Wisconsin DPI has resources to support adult compassion resiliency that can be accessed for free. |

Do not ignore signs of burnout, increased anxiety, or other mental health warning signs. Seek help from colleagues, administrators, professional organizations, medical professionals, family, friends, and others. |

Reflection and Application Activities

The following reflection and application activities were developed to build the knowledge, skills, and systems of adults so they can assist students with accessing, engaging, and making progress in age or grade level curriculum, instruction, environments, and activities.

-

Review and discuss the list of de-escalation and escalation examples above with your team.

-

Have you used any of these strategies with students? What were the outcomes or results?

-

Is there anything you would do differently if the same situation with a student were to occur again?

-

Is there a strategy missing from this list that you have found to be effective in de-escalating a student or students?

-

Is there a strategy you have used but have not found to be effective to de-escalate a student? Why do you think the strategy was not effective?

-

What training or support for school staff may be needed?

-

How do you know if you are using the strategy effectively or to fidelity?

-

What role does culturally responsive problem-solving and culturally responsive practice have on effective de-escalation strategies?

-

-

-

Are there patterns of if, how, and when adult responses to student behavior are used to either escalate or de-escalate student behavior based on students’ race or ability (e.g., disability category)?

-

What data and information is collected and analyzed to identify if there are race or ability based patterns for how adults respond to student behavior?

-

How might data help identify which adults need additional training and support to respond to student behaviors? Do you look at data on both successful and unsuccessful attempts of de-escalation to improve training and support for teachers?

-

How often is data disaggregated to ensure adults are responding to student behavior consistently across the school and district?

-

Does your data assist in identifying the most appropriate person (e.g. adult who has the best relationship with the student) to assist with prevention and de-escalation?

-

-

Discuss with your team how you can best support colleagues across your school or district to collaboratively and consistently use de-escalation strategies with students.

-

Review the Acting-Out Cycle. Reflect individually or discuss with a group how the Acting-Out Cycle applies to your own behaviors and preferences for support.

-

What are some triggers that cause you agitation?

-

When you are agitated, what are the behaviors from others that either escalate or de-escalate your agitation?

-

Consider how you validate a student's feelings throughout the acting out cycle compared to how you want others to validate your feelings when you are upset.

-

What does it feel like when someone tells you that “you should not be upset or hurt by something”?

-

Now consider how telling a student not to be upset, angry, sad, etc. makes them feel. Telling a person not to feel whatever they are feeling can be harmful and can strain a relationship. It is never acceptable to tell someone how they should feel. Always validate your students’ feelings. Validating a student’s feelings does not mean that you are validating the behavior. What language will you use for an individual student that you support to validate the student’s feelings and not the student’s behavior?

-

-

How do you feel when someone else physically enters your personal space or touches you when you are agitated or your anxiety is escalating?

-

How do you feel when someone interacts with you physically and you are not able to see or hear that person?

-

Imagine you are at the grocery store getting milk from the refrigerator and someone comes up behind you and touches your shoulder. What feelings do you have and how would you respond?

-

How might this scenario be similar to a student who is being physically redirected (e.g., from behind) and has physical, medical, social and emotional, cognitive, communication, or adaptive needs? Might that student respond at times as startled or in a way to protect their safety?

-

When is physical redirection helpful to a student and when might it escalate student anxiety and behavior?

-

-

-

How can students and adults in your school community better understand their own and each other’s unique and individual triggers and how the behavior of others can be either helpful to de-escalate or not helpful and escalate the Acting-Out Cycle?

-

Consider how local, national, and/or global events might impact your students. What preventative strategies could you use during times of social unrest that may prevent escalation of behavior?