Agricultural education is by no means new to Wisconsin: the Smith-Hughes act of 1917, which formally funded agricultural education, allowed countless students across the state opportunities to learn about horticulture, animal sciences, and natural resources.

Agriculture education tends to be associated with rural areas, not Wisconsin’s largest city. “Urban high school” and “agriculture school” might even be regarded as opposites. But for the past six years, Milwaukee’s Vincent High School has proved that agriculture-based education is relevant to urban youth.

Built in the 1970’s, Vincent was created as an agricultural school. Its agriculture focus waned in later decades due to funding issues. The program was revived in 2012 through partnerships among Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS), individual University of Wisconsin (UW) schools, Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC), local businesses, and a couple of the school’s science teachers. The program has flourished since its revival.

“We now have six agriculture teachers, who each oversee a pathway: animal science, horticulture, agribusiness, culinary arts, environmental science, and food science,” said Gail Kraus, Agriculture Outreach Specialist at Vincent.

Due to increased administration and staff supports, new access to facilities and additional outdoor space, and partnerships with UW schools and MATC, the program at Vincent encompasses a student’s four-year high school career. It kicks off freshman year with a required survey class which spends two and half weeks on each of the six pathways. The class gives students a taste of each pathway and allows them to decide which option they’ll pursue for the next three years.

“One of the best things we’ve done is offering students the survey course so they’re able to explore each pathway before committing to one,” said Kraus.

After choosing a pathway, students take more advanced coursework in their sophomore and junior years. In their final year, they work on an independent study project. While the animal science path is a popular choice, animal science teacher Monica Gahan remarks that students remain interested in all of the pathways.

It may be unexpected for an urban school to take such a strong agriculture focus, but it’s not uncommon in Wisconsin. Jeff Hicken, Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources Consultant for the Department of Public Instruction (DPI), says that schools in other urban cities like Eau Claire, Green Bay, Oshkosh, and the greater Madison area have agriculture programs.

Though much of the push behind statewide increases in agriculture programs may be market-based, the value of a Vincent education isn’t necessarily tied to a future farming career, or even a college degree in horticulture or animal sciences.

“On the whole, we are educating students who will be consumers, not farmers,” said Gahan. “It really boils down to how far removed we are from where our food comes from, which is an issue even in rural areas.”

Gahan summarizes an exercise she does with her students where she poses the question: “what happens if, starting today, we could no longer use, have, or consume animals or animal products?” She urges her students to break the hypothetical down, moving beyond the obvious.

“It goes as far as ‘there’s no NFL football, there’s no Super Bowl, there are no million dollar ads . . . students start realizing how important animals are to us, how we need to take care of animals. Will they grow up to be farmers? Probably not. But most people in rural areas won’t either.”

Yet, students are still getting passionate about agriculture and involved in opportunities outside of the classroom. From participating in research internships at out-of-state universities to attending the National FFA Organization Convention to showcasing animals for their communities, students are sampling the variety of opportunities that an education in agriculture brings to the table.

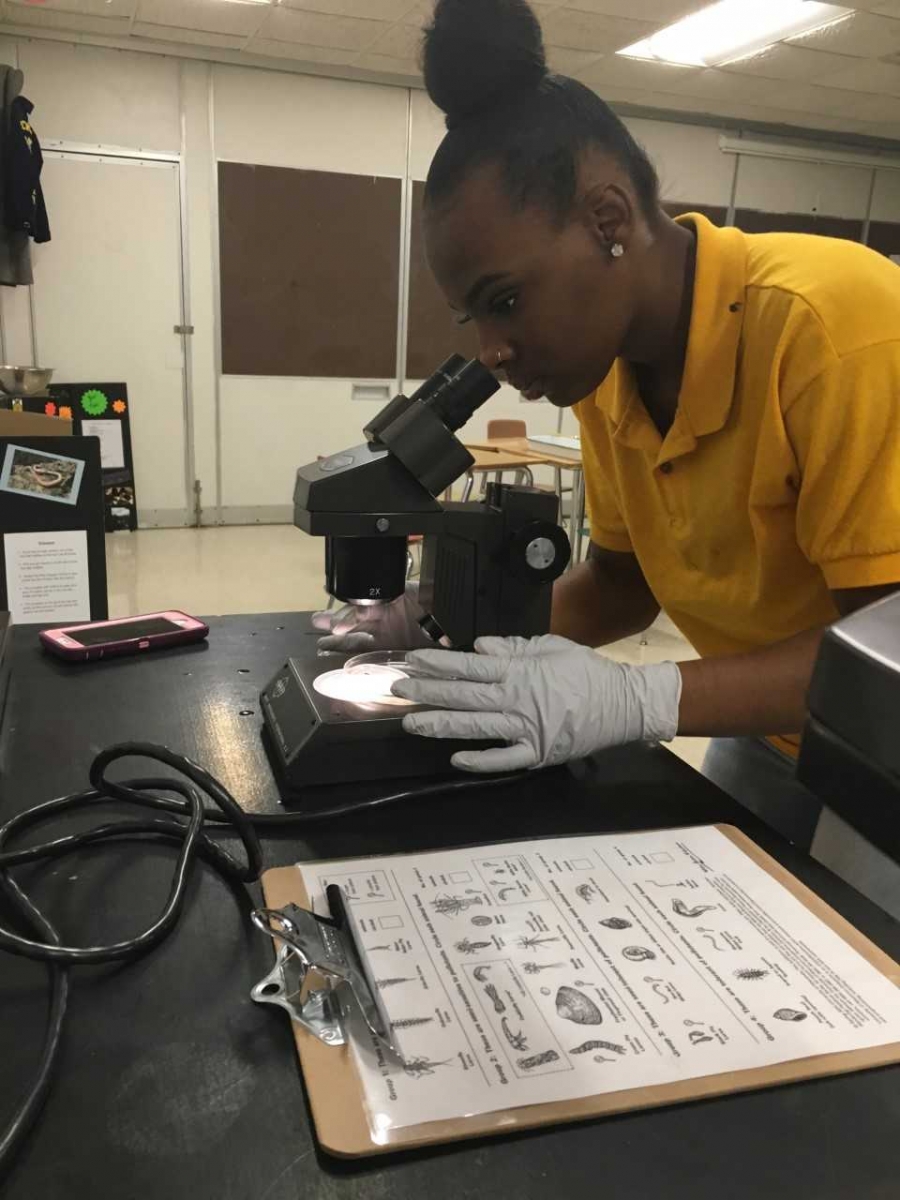

Students are also drawn to the program’s hands-on approach to learning. Each day is different, and students can expect to take trips to the school’s barn, greenhouse, or gardens during their class periods. For Gahan, curricula are dynamic, not tied closely to a textbook. If a cow has a calf during the weekend, she’ll film it and bring it to class, using the video to spur discussions about anatomy, calf-care, or other topics.

With an 80-acre campus, Vincent High has plenty of facilities that need maintenance, which older students help with during classes and independent work. The school has an animal room, garden, greenhouse, beehives, aquaponics and hydroponics, a barn with livestock, and a school café. Vincent is also in the process of fundraising for a food lab, and other facility updates and expansions.

The program has come a long way in six years, and Vincent staff expect that it will continue to grow. They hope to add a seventh pathway—Ag Power and Tech—and a seventh teacher to oversee it. With the success of the program so far, there are no doubts that Vincent is benefitting its students and community.

“We used to have some challenges with people questioning the relevance of agriculture, but the more that we’ve done with the students and the school to show the impact that agriculture has on our daily lives, the more it’s caught on,” Krause said. “We’ve been more diligent about making sure that students understand from the start why agriculture is important.”

“One of our biggest challenges now, really, is getting the word out about what the school is doing,” said Gahan. “People aren’t really resistant, and parents tend to be engaged and excited. How many other schools can you visit where your child will take you outside and show you a horse?”